How did Simetría-dos come to be?

Transforming our destiny is a patient and passionate construction, not without problems and contradictions.

That is why when two women who have become experts in the fields of art and science tell their story in the first person, the result is inspiring. Furthermore, what is related here is not a finished story, but rather that story’s drifts and confluences, its luminous and dark zones that, even now, upon reviewing them again, continue to cause us feelings of horror and sadness.

Patricia Bernardi is the founder of the Equipo Argentino de Antropología Forense [the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team, henceforth referred to by its Spanish acronym, EAAC] and Claudia Bernardi is an esteemed artist and professor who has built her career in the United States. Before turning 30, Claudia was already a renowned artist and educator in the place she was living in the United States, and Patricia, together with a group of fellow anthropology students was already laying the groundwork for the creation of for what would become the EAAF.

Between 1984 and 2014, Patricia and Claudia exchanged letters as a way of staying connected across the distance between Buenos Aires and the United States. In their correspondence they wrote about their shared past, their enigmatic present, their time at university, their loves, and more than anything, art and science.

We offer here a first glimpse into a personal and unique archive that has been preserved for decades by the Bernardi sisters and has not been shared until now. The heart of this project is the letters the Bernardi sisters exchanged throughout the 1980s. It is in those letters that they discuss the origins of the EAAF.

In addition to the letters, the archive contains a selection of photos, visual art, newspaper cuttings, and other memorabilia.

By assembling these assorted materials and using them to create a kind of dialogue between Claudia and Patricia based on text and images, we seek to offer a story that, despite being fragmented, tells a tale full of meaning that has been evolving and continues to evolve.

At the same time, some of symmetries in our ways of thinking ended up being surprising, at least to us. For instance, while one sister was beginning an exhumation in the Avellaneda cemetery, the other, at the other end of the world, was making artwork that consisted of burying clothing, evoking absences, and thinking about the disappeared from a political yet poetic point of view. These subtle consonances are, in retrospect, strikingly powerful, because they are evidence of how Claudia and Patricia were connected not only by blood, but also by a specific way of living and conceiving what they had experienced.

From this imperfect symmetry, imperfect like everything in life, we developed the conceptual approach to this website.

Suggestions for how to read the website:

On the timeline, we have placed a number of “meeting points” related to biographical, personal, and political events from Claudia and Patricia’s childhood up until a project on which they collaborated in 2014: a mural in the former Esma, where the offices of the EAAF are located in Buenos Aires, that was painted by the relatives of disappeared people whose remains were recovered by the Team.

The red dots below the timeline mark Patricia’s paths, which are connected to the earth, its depths, and its secrets.

The yellow dots above the timeline mark Claudia’s paths, which are connected to how Patricia’s work was seminal to Claudia’s artistic work.

The blue dots indicate the symmetries and confluences on the life paths of the two sisters.

And so, this first section of the story appropriately opens with a photo from the siblings’ childhood in which we see Claudia running with her younger sister, Patricia, right behind her, in the garden of their house in Güemes 2866, Florida, Buenos Aires, around 1963.

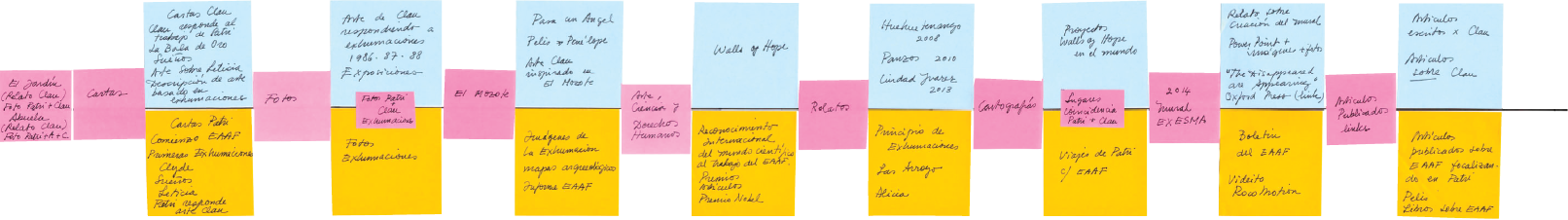

At the top of the page, we also show readers what we affectionately call “the little slips of paper,” which comprise a structure created out of post-its, sticky notes that despite their delicate nature became a kind of backbone, a powerful force, as we discussed our ideas for this project that we carried around in our heads and our hearts. “The little slips of paper” represent our thoughts at the time when the idea for the page (and how it might be rendered) was being envisioned.

A few editorial comments:

As noted above, this is a first glimpse at an archive that has not been viewed before, and for that reason, it continues to be unearthed, worked on, classified, and revealed. In each section, we know there is a possible story that could be developed or explored in greater depth.

The letters shared here are but a small part of the original archive. Claudia and Patricia prioritized which ones would be exhibited after an exhaustive selection process in which they chose those missives that would help to begin weaving together and providing meaning to this unique story. The original syntax has been preserved as much as possible with only a few small changes to aid the reader’s understanding. Notes are included in cases where it is necessary to provide additional information.

Members who contributed to this project:

The decisions that have been made are the product of an ongoing process of selection, editing, and writing that we are doing in collaboration with the journalist and poet, Ivana Romero. The work Ivana has done with us to date has allowed us to present this first synthesis of materials to you, which is open to new interpretations and possibilities. Ivana has been our friend for more than two decades, but that was not the main reason we wanted to work with her. Apart from her talent and her poetic sensibilities (where words are sometimes not enough, the silence that poetry proposes is eloquent, and it is from that space that we would like our page to be approached), Ivana was born in 1976. Her generation and ours are in constant dialogue with the goal of continuing to construct memory, truth, and justice.

In addition to Ivana’s careful work, we must mention the discerning eye of designer Fabián Muggeri, who created this web page using programming by Mariano Arias.

More about Ivana:

She was born in 1976 in Firmat, in the province of Santa Fe. She is a poet, journalist, and author. She has a bachelor’s degree in social communication from the Universidad Nacional de Rosario and a master’s in journalism from the Universidad de San Andrés in Buenos Aires.

She is the author of the following books of poetry: Caja de costura (Eloísa Cartonera, 2014) and Ese animal tierno y voraz (Caleta Olivia, 2017). She also wrote the autobiographical chronicle, Las hamacas de Firmat (Editorial Municipal de Rosario, 2014).

She regularly publishes journalistic and non-fiction pieces in various media, among them Radar y Radar Libros (Página 12), Las 12, Clarín Cultura and Revista ñ. In the last two publications, she also had an editorial role.

She teaches Poetry I and non-fiction classes in the Art of Writing program at the Universidad de las Artes (UNA). She also teaches introductory classes in that program.

Currently she is translating essays by May Sarton, the North American poet originally from Belgium. She is also finishing another book of poetry and is writing a book about Bruce Springsteen, of whom she is a great fan.

Work group:

Idea for the project and its coordination: Claudia Bernardi and Patricia Bernardi

Editing of texts and primary consultant: Ivana Romero

Web design: Fabián Muggeri

Web programming: Mariano Arias

English translation: Alison Ridley

About translator Alison Ridley:

Alison was born in England but grew up in France, Norway, the United States, and Venezuela. She received her doctorate in Spanish from Michigan State University in 1991 and she teaches at Hollins University in Roanoke, Virginia, U.S.A. She has published book reviews and academic articles on the plays of Buero Vallejo, but she is also a translator. Since 2014, she has translated several books and essays written by Chilean American author and human rights activist, Marjorie Agosín. She met Claudia for the first time about ten years ago when Claudia was at Hollins giving some presentations about her art and her work in El Salvador with Walls of Hope.

Translating Simetría-dos has been a great privilege for Alison, who hopes that, thanks to the translation, Claudia’s and Patricia’s important work will have a broader reach.

This project has been made possible thanks to the Beca Creación 2021 [Creative Scholarship] granted by the Fondo Nacional de las Artes [National Arts Fund], which is overseen by the Ministerio de Cultura de la Nación [Argentina’s Ministry of Culture].

For permission to reproduce photos or other images, please contact us beforehand and be sure to cite the source: Archivo Claudia y Patricia Bernardi-Proyecto Simetrías.

We welcome you to Simetría-dos.

Infancy

Patricia and Claudia

Claudia holding Patricia in her arms at the house at Tacuarí 1215, San Telmo, 1958.The Bernardi Family

At the beach in Necochea. Claudia is the girl in the middle and Patricia is being held by her mother, 1959.The Girls with Their Grandmother

The grandmother, Doña María B. de Carracedo, was a feminist before the concept was invented. When we became orphans, Patri was 13 and Claudia, 16. Their grandmother was not a great source of support or emotional shelter, but she was, and continues to be, an unquestionable inspiration, a model who pointed us in the uncommon direction of becoming independent women who would make our own personal and professional decisions. In the letters, the grandmother (sometimes referred to as “abuels”) peers out from the fog of Alzheimer that plagued her during the last decade of her life. Plunged into memory loss, she was no longer the undisputed family matriarch; instead, she became a tender and fragile being.

Photo taken in the Monserrat apartment, 1979.

Photos of Patri and Claudia

Here are a series of shared moments in places around the world.

El Mozote, 1992

Patricia and Claudia in October, 1992, when the exhumation of the El Mozote massacre began. El Salvador.Transfer to Hawzen, Northern Ethiopia, 1994

From left to right: Anahí Ginarte, Claudia, and Patricia.Hawzein, Ethiopia, 1994

This was the “look” they adopted to conduct the exhumations due to the many flies at the site.The El Mozote Massacre, El Salvador, 1981

The El Mozote massacre was one of the most egregious cases of human rights violations committed during the twelve years of the civil war in El Salvador.

Between December 6 and 16, 1981, the Salvadoran army began an offensive in the northern part of the region of Morazán. It lasted ten days and was dubbed “Operation Rescue.” The military campaign was carried out principally by the Batallón de Infantería de Reacción Inmediata (BIRI) Atlacatl [The Atlacatl Rapid Deployment Infantry Battalion], that had been trained by U.S. advisors as an “elite” counterinsurgency battalion.

The objective of “Operation Rescue” was to eliminate guerrilla presence in a small portion of northern Morazán. The guerrillas (FLNM: Frente Farabundo Martí de Liberación Nacional or the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front) had a training camp in that region, close to the hamlet of El Mozote, called “La Guacamaya.”

During the first days of the military operation, there were several clashes between the army and the guerrillas, and the latter withdrew from the region on December 9. Nevertheless, the Salvadoran army’s Atlacatl battalion murdered, tortured, and committed other acts of extreme violence against the civilian population in the canton of El Mozote and the surrounding rural areas.

According to the official register of victims, 986 civilians were murdered indiscriminately; more than half of them were children. Rapes and other acts of sexual violence were also systematically committed against women, girls, and boys.

The exhumation in the hamlet of El Mozote unearthed 143 people, 131 of whom were under the age of 12. Two hundred and forty-five spent gun cartridge cases were also recovered. A study conducted by a ballistics expert found that at least 24 shooters participated in the incident.

The EAAF did the exhumation work in 1992. While not an official member of the EAAF, Claudia Bernardi participated in the exhumation because of her ability to draw maps and graphics that would help the team to delimit the work areas. That experience was fundamentally important to Claudia’s own work, as it served as the impetus for what would later become “Walls of Hope,” a community arts project that Claudia developed with a group of Salvadoran artists and that has been replicated around the world.

Maps

These two maps show El Salvador in Central America. In the graphic to the right, the hamlet of El Mozote in the Morazán Department is highlighted with a red dot in the top right-hand corner.The El Mozote Massacre, 1981

Photographic documentation of the El Mozote massacre, December 1981. Photo by Susan Meiselas.Freehand Graphic of the Hamlet of El Mozote

This drawing was done by David Morales, a lawyer from Tutela Legal, using information gathered from various interviews conducted with survivors.Site #1: The First Site Excavated in the Hamlet of El Mozote, 1992

Ground plan of Site #1, dubbed “the Convent,” where the exhumation took place in 1992. The archaeological design was a system of grids and quadrants traced on paper in order to be able to locate all of the findings three dimensionally later on. Graphic by Claudia Bernardi.Site #1, 1992

The delimitation of the exhumation site was done after collecting testimonies, comparing information, and drawing archeological maps.Archeological Maps

Claudia maps the contours and surface area of Site #1, “the Convent.” Even though she may not be an official member of the EAAF, she participated in a number of their missions where mapping and drawings had to be done by hand since, back then, more sophisticated technology was not available.Site #1, El Mozote, 1992

Identification of the base wall of the original “Convent” building, where the massacre took place.Clearing the Plot, 1992

The ground was carefully weeded and when the soil was ready, the sediment was gently removed until the first bones and other evidence were reached.The Findings, 1992

Archeological techniques made it possible to uncover the skeletons whole along with associated evidence (clothing, ballistic evidence, etc.).Photographic Relief

Vertebrae and ribs recovered from inside a small article of clothing, confirming the suspicion that the murdered person was very young.On the Plank

Patricia works on the exhumation supported by a plank between the base walls of the original building.Grindstone

Claudia working inside Site #1. To the left is a grindstone under which the ossified remains of a young girl were found.Archeological Techniques

Claudia using a brush to clear away soil from one of the skeletons uncovered in Site #1.Art Inspired by the El Mozote Massacre

Works by Claudia Bernardi mainly using the fresco on paper technique.

Under the Skin

Pigments are colored powders of enormous intensity that refuse to remain on the paper. They are adhered in multiple layers that interact with one another. (1996, 30”x60”)What Terrible Luck, Girl

In the fresco on paper technique, the pigment becomes the paper through pressure being applied by an engraving press. (1996, 30” x 42”)The Weight of Evil

In the fresco on paper technique, pigments are applied directly to the surface. The pigments become the wall. (1995, 30” x 42”)Stains Leave Marks on the Vessel of the Soul

Burying and unearthing images brought to life what Claudia had seen in El Mozote. (1999, 30”x60”)Dress of Predicaments

Life draws a tree and death draws another” (from a poem by Roberto Juarroz). (2004, 30” x 42”)A Body Full of Gazes

One must look with one’s eyes, hands, feet… The whole body can see. (2007, 30” x 42”)Agenda for an Attentive Woman

I heard someone tell Rufina Amaya Márquez, the sole survivor of the El Mozote massacre, that after everything that had happened, she could grab snakes without being afraid of them. (2007, 30” x 42”)City of Threats

Imaginary cities and ones we know well are filled with threats and bewilderment. (2007, 30” x 42”)Zora, the City of Omens

Inspired by Ítalo Calvino, Zora searches through streets that have existed, have disappeared, and have become omens. (2004, 30” x 42”)Cartographies of Impossible Loves

Maps, poems, names, texts, photos, are interspersed among the pigments. They are revealed or they remain hidden. (2004, 30” x 42”)Amputated Hands

In the fresco on paper technique, images are traced with spoons and teaspoons. (2004, 30” x 42”)Here Is Where It All Begins

In an exhumation the earth is removed from human remains using teaspoons and spoons. (1999, 30” x 30”)The Nobel Wing of an Angel

No one survived in El Mozote. The people of Morazán say that when there is silence it is because angels are passing by. (1999, 30” x 30”)Argentina

In our country, the EAAF has recovered the remains of around 1,700 people, approximately 950 of whom have been identified.

Patricia was one of the founders of the EAAF in 1984 and continued that work until 2019. She worked to exhume, identify, and return the victims of forced disappearances during the illegal repression that occurred between 1975 and 1983. She also provided evidence at numerous human rights abuse trials around the country.

In 2014, Claudia facilitated a project titled “The Disappeared are Reappearing,” which was a collaborative and community-based mural created by relatives of disappeared people whose loved ones’ remains had been recovered thanks to the exhumation and DNA work developed by the EAAF in the EX-ESMA (ESMA, Escuela Superior de Mecánica de la Armada / Navy School of Mechanics).

In 2014, Claudia facilitated “How Does One Draw the Truth?” a collaborative and community-based mural created by the relatives of victims of police brutality and the Argentine penal system. Museum of Art and Memory, Provincial Commission for the Memory of the Province of Buenos Aires, and the Museum of Art and Memory of the Province of Buenos Aires, La Plata, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

In 2014, Claudia facilitated, “The Knot,” a collaborative and community-based mural created by human rights activists, relatives of the disappeared, and the personnel of EX-ESMA, the former clandestine detention, torture, and extermination center in Buenos Aires.

El Salvador

The EAAF was summoned to work in El Salvador in 1991 on forensic investigations related to that country’s civil war (1980-1992), which left in its wake close to 80,000 dead.

The EEAF’s work continues there today. They collaborate in investigations carried out by various NGOs. The first work done by the EAAF on the exhumation and analysis of skeletal remains from the civil war took place in 1992 in coordination with the Office of Legal Guardianship, the legal Office of the Archbishopric, and the United Nations Observer Mission.

According to research done by various sources, the Salvadoran army murdered approximately 1,000 civilians who lived in the hamlet of El Mozote and five other neighboring hamlets in the department of Morazán, making it one of the largest massacres in contemporary Latin America. The scale of the work was a challenge for the EAAF given the complexity of the place and the long fight with the Salvadoran state to allow the investigation to continue.

The attention to detail that the work required led the EAAF to call in Claudia Bernardi as an independent consultant who would oversee the surveying of all the evidence, both ballistic and personal effects. The exact location of each piece of ballistic evidence in relationship with the skeletons turned out to be forensic evidence used to establish the manner of death of many of the victims found at Site #1.

The results of the forensic work carried out by the EAAF in 1992 were incorporated into the report that was submitted to El Salvador’s Truth Commission (1992-1993). In all, 143 remains were recovered, 131 of which belonged to children under the age of 12.

In 2018, the forensic evidence was presented before a public hearing in the Second Court of First Instance, condemning the Salvadoran state for the massacre and ordering it to implement reparation measures.

Ethiopia

In 1993, the Carter Center contacted the EAAF to ask them to assist the Addis Ababa district attorney’s office with certain forensic investigations that needed to be performed.

In 1994, Patricia, as a member of the EAAF, and Claudia, as an independent consultant, worked together in the town of Hawzen in Tigray. According to numerous testimonies, the Ethiopian air force bombarded the town for six hours on June 22, 1988. It was a Wednesday. In other words, it was market day, and the town was filled with people from the region. A significant part of the town was destroyed during the bombing. It was impossible to ascertain how many people had perished, principally because most of the victims had come from other regions and their bodies were taken back to their towns or buried in mass graves in various places in Hawzen.

Guatemala

The number of forced disappearances in Guatemala over the last four decades is greater than in any other Latin American country. Since 1976 when the internal conflict began, approximately 45,000 people are thought to have disappeared. Most of those people disappeared from farming towns between 1978 and 1986 during the counterinsurgency campaign against guerrilla groups directed by the military governments of General Lucas García (1978-1982), General Efraís Ríos Montt (1982-1983), and General Óscar Humberto Mejía Vítores (1983-1986).

As an EAAF consultant, Patricia participated in forensic missions in the Quiché department in 1991, 1992, and 1993. Between 1994 and 1995, Claudia joined this work as an independent consultant in the case of “The Massacre at Dos Erres” in the El Petén department.

Claudia and the artists from Walls of Hope facilitated collaborative and community-based art projects with the civilians who were victims of violence during the armed conflict:

2007, collaborative and community-based mural with victims of the Ixil, Ixcán, Nebaj, Rabinal, and Chichicastenango massacres.

2008, Huehuetenango, collaborative and community-based mural with indigenous women, survivors of sexual violence.

2009, Cobán, paper sculptures created by indigenous women, survivors of sexual violence and sexual slavery.

2009, Rabinal and Plan de Sánchez, collaborative and community-based mural created by victims of torture and the massacres in Rabinal, Plan de Sánchez, and Río Negro, Baja Verapaz.

2010, Panzós, collaborative and community-based mural created by the victims of the Panzós massacre, Alta Verapaz.

Mexico

Patricia, as an EAAF consultant, worked on the identification of the skeletal remains of murdered and disappeared women in Ciudad Juárez and the city of Chihuahua between 2005 and 2008.

Between 2013 and 2014, Claudia and the Walls of Hope artists facilitated collaborative and community-based art projects: a mural and a workshop on paper sculptures, created by young people between the ages of 13 and 18 who had been affected by the consequences of violence in Ciudad Juárez. These collaborative art projects arose from an initiative and invitation from the CICR (Comité Internacional de la Cruz Roja / the International Committee of the Red Cross) and the Mexican Red Cross.

Bosnia

In 1998, Patricia, as a member of the EAAF, served as a forensic expert at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in the territories of Croatia, Bosnia, and Kosovo.

Serbia

In 2003, Claudia exhibited an individual show, “Claudia Bernardi: Boja Vremena / The Color of Time.” Installation, DAH Teatar, Belgrade, Serbia.

In addition, she proposed collaborative and community-based workshops in theater and visual arts with the victims of the war in the Balkans, victims of the Mostar massacre in Bosnia, Women in Black, and Serbian artists and activists.

Canada

In 2008, Claudia directed, alongside Julie Jarvis, an artist and producer, a multidisciplinary project incorporating installation art, sculpture, paintings, videos, dance, theater, and poetry. Walls of Hope, Canada, was created by 38 young people between the ages of 13 and 27 who were recent political refugees seeking political asylum, special needs youths, youths who had come from the Canadian criminal system, and indigenous peoples from the First Nation tribe.

USA

Between 2014 and 2018, Claudia and the artists from Walls of Hope facilitated the creation of collaborative and community-based murals by undocumented, unaccompanied, migrant minors from Central America incarcerated in juvenile detention and maximum-security facilities in the United States. “Labyrinths on the Border / The Train of Dreams,” “The Tree of Life,” “Second Chances,” “Let me Bloom Again,” and “Life Holds More than I Can See Right Now,” are murals that amass the visual testimonies of these young migrants. In the murals they set down their personal and communal memories and the story of why they left their countries of origin due to violence, poverty, and drug trafficking.

In 2016 and 2017, Claudia facilitated two collaborative and community-based murals painted by children, youths, and adults who are members of the Yurok Tribe in the Klamath river region of northern California. One of the murals is on permanent display in the Yurok tribe’s courthouse.

Honduras

In 1992 and 1993, as a member of the EAAF, Patricia was invited to the capital of Honduras, Tegucigalpa, by the special district attorney’s office focused on human rights to provide advice on forensic work related to political disappearances that occurred in the 1980s and 1990s.

Claudia was invited in 2021 by the Promoción del Empleo y Prevención de la Violencia Juvenil (the Promotion of Employment and Prevention of Youth Violence) and the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH (German Agency for International Cooperation GmbH), to develop a consultancy to address the creation of collaborative and community-based workshops on muralism, woodworking (and making furniture), and art created with recyclable materials. These workshops were to be directed at young people affected by violence. This consultancy, which was initiated by the mayor’s office in Tegucigalpa, included a proposal for the workshops to be replicated in other Honduran municipalities.

Panama

Since 1993, the EAAF has worked in Panama on the identification of people who disappeared between 1968 and 1989. Patricia served as an international consultant in 1992 and 2001.

Colombia

In 2009, Claudia and Walls of Hope facilitated two collaborative and community-based mural projects in Cocorná, Antioquia, with members of AVVIC (Asociación de Víctimas de Violencia de Cocorná / The Cocorná Assocation of Victims of Violence), survivors of the effects of landmines, and victims of forced exiles and political violence during the armed conflict in Colombia.

As of 1996, The Perquín Art School and Open Studio / Walls of Hope, settled in Sincelejo, adhering to the efforts of “Sowing Peace” a community development organization. The Perquín Art School develops, implements, and disseminates collaborative and community-based art projects echoing the proposals in the Peace Accords signed in 2016, putting an end to the 52-year armed conflict.

In 2017, Walls of Hope facilitated “The Hard Work of Remembering,” a collaborative and community-based mural created by the artists from Walls of Hope who were expanding the “Perquín Model” working with survivors of the La Libertad massacre (Sucre, Colombia) as part of the Peace Accords, which mandated community building through art. Another such project was “Finding a Path to Peace,” a collaborative and community-based mural created by Walls of Hope artists working with displaced victims and victims of forced exile from Mampuján (Sucre, Colombia).

In 2019 in the Colosó community, Claudia and Walls of Hope facilitated a collaborative and community-based mural painted by former combatants of FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia / Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) and civilian victims of violence during the armed conflict.

Ecuador

In 2015, Patricia, as a member of the EAAF, served as a forensic consultant for the Criminal and Forensic Sciences Laboratory (Ministry of the Interior) to evaluate the state of forensic investigations in Ecuador.

Brazil

Since 1991, the EAAF has been assessing human rights organizations, investigative commissions, and local authorities, in the investigation into the fate of disappeared people during the last military dictatorship in the country, between 1964 and 1985. Patricia served as a forensic consultant in the Araguaia and Perus cases in 1996, 2004, 2015, and 2016.

Bolivia

Patricia, as a member of the EAAF, participated in the search for, and exhumation and identification of, the remains of Ernesto Che Guevara between 1995 and 1997.

Paraguay

From 2005 to 2011, the EAAF collaborated with the Paraguayan authorities and the relatives of about 400 people who disappeared from that country between 1954 and 1989. Patricia served as a forensic consultant in 2009, 2015, 2016, and 2018.

Sierra Leone

In 2002, at the request of the Office of the High Commissioner of the United Nations, Patricia, along with other members of the EAAF, carried out a preliminary investigation of the alleged deaths and burial sites of victims of the armed conflict in Sierra Leone.

Congo

In 1997, the EAAF coordinated forensic efforts with the United Nations Center for Human Rights and the International Forensic Team of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, dedicated to investigating serious human rights violations committed against refugees. Patricia participated in this first assembly and in 2002 she returned to participate in an evaluation mission at the request of the Office of the High Commissioner of the United Nations.

Northern Ireland

In 2011, Claudia facilitated and directed a collaborative mural project in Belfast during the riots in the Ardoyne district. The participants were Protestant and Catholic children from the Wheatfield (Protestant) and Holy Cross (Catholic) primary schools located on Ardoyne Road to the west of Belfast.

Germany

In 2013, Claudia and the artists from Walls of Hope facilitated the creation of a collaborative and community-based mural at the University of Osnabruk. The participants in this project were social work students and migrant women from Eastern Europe, Africa, Latin America, and the Balkans.

Switzerland

In 2012, Claudia and the artists from Walls of Hope facilitated the project “Le Mur de l’Espoir” (“The Wall of Hope”) in Monthey. It was created in collaboration with Amnesty International. The participants included 93 refugees, migrants, and victims of forced exile from 25 countries in Latin America, Africa, and Eastern Europe.

In 2013, Claudia and the artists from Walls of Hope facilitated the project “Le Mur de l’Espoir” (“The Wall of Hope”) in Fribourg. It was created in collaboration with Amnesty International. The participants were refugees, asylum-seekers, and victims of forced exile from Afghanistan, Congo, Sri Lanka, Eritrea, Somalia, and Tibet.

Romania

In 1993, upon the request of the district attorney of Bucharest, Patricia, along with two other members of the EAAF, undertook an investigation into the discovery of skeletal remains in the city of Caciulati resulting from with the political violence of the 1950s. Said mission was requested by the attorney general of Romania and the National Institute of Legal Medicine in Bucharest.

Georgia

Since 2014 the members of the EAAF have traveled to Georgia and Abkhazia at the request of the CICR (Comité Internacional de la Cruz Roja—The International Committee of the Red Cross) in relation to the conflict between Georgia and Abkhazia, 1992-1993. Patricia participated as a forensic consultant in 2014, 2016, and 2017.

Abkhazia

Since 2014 the members of the EAAF have traveled to Georgia and Abkhazia at the request of the CICR (Comité Internacional de la Cruz Roja—The International Committee of the Red Cross) in relation to the conflict between Georgia and Abkhazia, 1992-1993. Patricia participated as a forensic consultant in 2014, 2016, and 2017.

Japan

In 1995, Claudia was invited to Japan by the International Center for Peace in Hiroshima during the events to commemorate 50 years since the atomic bomb tragedy in 1945. Claudia organized and exhibited a show by Salvadoran and Guatemalan artists, survivors of political violence during the civil wars in Central America.

East Timor

The EAAF worked in East Timor between 2001 and 2011 training The United Nations Serious Crimes Unit and investigating the Santa Cruz massacre (1991) as well as other cases of human rights violations committed during the Indonesian occupation of East Timor. In addition, Patricia served as a forensic consultant in 2001.

The Disappeared are Reappearing: A Collaborative Community Mural in the EX-ESMA

“The Disappeared Are Reappearing” is a collaborative community mural project designed, carried out, and completed by the relatives of victims of State terrorism in Argentina in the ILID building (Iniciativa Latinoamericana para la Identificación de Personas Desaparecidas or Latin American Initiative for the Identification of the Disappeared) in the EX-ESMA, the largest clandestine detention, torture, and extermination center in Argentina.

The relatives who participated in this project had recovered the remains of their loved ones thanks to the tenacious work of the EAAF. Using forensic anthropology and other scientific techniques, and working in close collaboration with the relatives, the EAAF seeks to identify the exhumed remains, thereby contributing to the search for truth, justice, reparation, and the prevention of future human rights violations.

Patricia is part of the EAAF, charged with conducting the exhumations, and she became very close to many of the relatives during the process of restitution.

Claudia was the facilitator and director of this collaborative community art project.

The lives of these two sisters can be found in perfect symmetry in this mural. Patricia’s meticulous and deliberate work of unearthing the disappeared so they can reappear is complemented by Claudia’s work with the relatives of those who were disappeared and silenced, to paint a visual history that narrates memories, the lived experiences, and the hopes of their loved ones who they have searched for and now found.

Symmetries: Photo Gallery

The Family Artists

The family artists designed, painted, and finished the mural collaboratively and communally.Our Small Bones

This image conveys the intimate, delicate, and tragic moment when the relatives received the remains of their loved ones for whom they had searched for over 40 years.November Mural

In November 2014, a few months after the original mural was completed, another group of relatives of disappeared people congregated int eh ILID building of the former ESMA to extend the mural.Incorporating Windows

This new section of the mural included the challenge of incorporating in the mural the windows that were part of the wall.November Family Artists

The November mural included 25 relatives of disappeared people. The youngest artist was three-year-old Rosita.Patricia and Claudia Bernardi: Symmetries that Close and Open at the Same Time

In this mural, the lives of these two sisters meet in a symmetry in which the work of Patricia, who unearths the disappeared so they might reappear, and Claudia who, with the relatives of those who were disappeared and silenced, paints a visual history that narrates where experiences, pain, and hope coexist.-

bio claudia

-

letters

- Berkeley, April 12, 1985

- October 24, 1986

- Postcard, March 1987

- October 22, 1987

- August 25, 1988

- December 28, 1988

- February 13, 1989

- letters claudia

We present here a selection of letters from the many that are a part of the original archive. We have edited the letters minimally, only to aid in the reader’s comprehension and to preserve the clarity of the original materials.

-

pictures

- Pictures

- pictures claudia

Series of photos of Claudia where biographical and artistic aspects are linked.

-

art,

science and

h.r. -

stories

-

articles

-

introduction

-

pictures

A series of photos of the Bernardi sisters from their childhood to the work they did together.

-

el mozote

-

mapping

-

mural

ex-esma -

contact

-

bio patricia

-

letters

- letters patricia

- 1984 S/F

- March 20, 1985

- May 9, 1986

- February 8, 1987

- March 5, 1987

- March 13, 1987

- May 19, 1987

- September 25, 1987

- October 7, 1987

- October 31, 1987

- January 7, 1988

- Reverso de sobre. Febrero 22, 1988

- May 4, 1988

- May 21, 1988

- October 18, 1988

- March, 1990

The following is a selection of letters from among the many that make up the original archive. The editing criterion aimed at preserving the freshness of the original materials, restoring some aspects that help reading comprehension.

-

pictures

- pictures patricia

- Avellaneda Cemetery, Argentina

- Laboratory Work

- Clyde C. Snow

- The Beginning of the EAAF

Series of photos of Patricia, the work of EAAF and the team's founder, Clyde Snow.

-

stories

-

articles